Her Story: Ladies In Literature is a special, month-long series on Pop! Goes The Reader in which we celebrate the literary female role models whose stories have inspired and empowered us since time immemorial. From Harriet M. Welsch to Anne Shirley, Becky Bloomwood to Hermione Granger, Her Story: Ladies In Literature is a series created for women, by women as thirty-three authors answer the question: “Who’s your heroine?” You can find a complete list of the participants and their scheduled guest post dates Here!

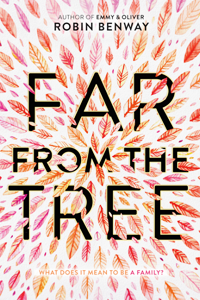

About Robin Benway

I’m the author of six novels, including Emmy & Oliver, Audrey, Wait! and the AKA series. My newest book, Far From the Tree, will be in stores October 3, 2017. I live in Los Angeles with my extremely stubborn shih tzu, Hudson. I like cooking, puppies, and coffee, but not in that order. We should be friends.

On the last day of fourth grade, my teacher gave out superlative awards to each of her students. When I brought mine home, my dad got so emotional that his voice shook.

“Out of all the awards you could have brought home,” he said, “this means the most to me.”

My superlative? Most Considerate of Other People’s Feelings.

I wish I still had that award. I have no idea where it landed, maybe in a box of old school art and awards that’s in the back of my closet. I’m too lazy to go through it now, so maybe we’ll never know. But if I did have it, I would take it out and write this the bottom: “Make sure they’re considerate of your feelings, too.”

Being a twelve-year-old girl is hard. It is fucking hard. Twelve is potential energy finally becoming kinetic, power slowly unleashing itself in ways that we couldn’t expect or control. Twelve-year-old girls spend their entire lives being told that they’re too quiet, too bossy, too ugly, too pretty, too smart, too dumb, and then they get a taste of what it feels like to be powerful, to be able to affect someone with a comment or a look or a cold shoulder, and it’s like heroin.

The wheels start to come off of friendships at twelve, relationships that were formed in the preschool sandbox suddenly torn apart in the middle school cafeteria for reasons that nobody can quite pinpoint, but feel very important at the time. And that’s what happened to me. I was too tall, too fat, too weird. When I see pictures of myself at twelve, I’m always confused by the disconnect between the girl in the photo and the girl in my head. I expect to see a monster and instead see a perfectly fine almost-teenager whose bucked front teeth could have reached out and shaken your hand. (Thanks for the braces, Mom and Dad. I owe you one.) Kids said terrible things to me, whole sentences that I can still remember with the sort of pristine clarity that I wished I had used to retain compliments instead.

And so I retreated into books. Well, not books, but worlds. One world, actually: Stoneybrook, Connecticut. My dad used to see me reading the pastel-colored paperbacks with titled lettering that resembled children’s blocks and roll his eyes. “You need to read the classics,” he would say, but he was a middle-aged man who had grown up in blue-collar Connecticut with three brothers. He didn’t know about the inner workings of twelve-year-old female life, how the classics didn’t mean anything to me when I was nearly crippled by the anxiety of going to school every morning. I needed stories where twelve-year-old girls stayed friends, didn’t make each other cry, worked together and had fun and made Kid-Kits. Also, all the classics were about boys. I’ve always been surprised that “Lord of the Flies” was about boys. It feels inaccurate.

Everyone had their favorite Baby-Sitter, but for me, Kristy was too bossy, Mary Ann too timid (though I envied her cat Tigger), Mallory and Jessi too young. Dawn, even though she was a California girl like me, was too easy breezy, and her fanaticism for tofu left me wary. Stacey McGill was diabetic and her stories about being in the hospital hit too close to home because my own father was diabetic and spent a lot of time in the hospital, too. I read Baby-Sitters Club to escape, not to recall that hospital smell of urine and antiseptic, the harsh blue flicker of fluorescent lights, a beeping machine that served as a steady reminder of the difference between living and being alive. (Now, in a delightful twist of irony, I’m a Type 1 diabetic, too. I still can’t read Stacey’s stories.)

Claudia Kishi was my favorite. I envied her independence, her artistic ability, her nonchalance at being a terrible speller. I don’t know if it’s fair to call anyone from Stoneybrook street-smart, but Claudia had the sort of attitude that I desperately wanted for myself, a straight-A student whose stick figures were always lopsided. Claudia wore outlandish clothes and did not care. She made her own jewelry. Claudia, horror of horrors, wanted to be different. Claudia did Claudia, and you were either on board the train or it was leaving you back at the station. (Sorry, Janine.)

But my favorite thing about Claudia was that she hid junk food around her room for her friends to eat during BSC meetings. She even had healthy snacks for Dawn and Stacey, who wouldn’t and couldn’t eat sugar, respectfully. That was so nice! That was so considerate of others! I used to legitimately wonder how Claudia’s bedroom never had an ant infestation because it was basically a sugar empire, but I always loved how the cool girl could also be so kind.

When I was a college sophomore at NYU, I traipsed through the snow one February afternoon to go to a recitation taught by my TA. Only one other girl showed up (let’s call her “Emma”), one of those girls who I shied away from in class because she seemed so cool, so pretty, so aloof. Being an awkward twelve-year-old can give you a certain kind of mental war wound that doesn’t go away for a while, and I avoided popular girls like the plague.

The three of us sat around talking for a while, and eventually the conversation shifted to childhood and teenager-dom, and how all three of us had been teased for being overweight when we were younger. And then Emma said, “It made me a much kinder person,” and to this day, I can’t think about those words without tearing up because I know exactly what she meant: The slice of people’s words had cut so deep that she would do anything to keep someone else from feeling that sort of pain. There’s a certain kind of empathy that’s born from being made to feel less than, and when Emma said that, the TA and I just nodded.

I didn’t see it at the time, but now when I think of Claudia, this is what I see in her, that sort of empathetic kindness. I mean, this girl was alone: A bad speller in a family of literal geniuses, a budding artist who had to buy all of her own painting supplies, a Japanese-American teenager in a town where no one else looked like her. (There are currently over 100 BSC books, not to mention dozens of Super Special Mysteries and Adventures, so I hope that there are more Asian-American families in Stoneybrook now. The books that I read growing up were lacking.) Even her best friend Stacey moved back to New York for a while. When I think of Claudia stashing snacks away for Stacey, I see a girl that knew what it was like to be left out, and it breaks my heart.

It’s easy to look back on those years now and think ruefully upon them. Me, a grown woman on the cusp of turning 40, with a career that I never thought I’d have, an apartment that feels like a home, a family that makes me so happy I sometimes want to cry because I don’t know what to do with all of the joy that they give me. It’s more than I ever thought I could make for myself, and sometimes I like to imagine Claudia as an adult making a life for herself, too: running a gallery in Soho, maybe, or tutoring kids who also have abysmal spelling, or running a successful jewelry shop on Etsy with Janine as her accountant. On the page, she never got to leave Stoneybrook, but I know she’s somewhere, buoyed by the millions of readers like me who desperately needed the sort of friendship she gave us. There is no doubt in my mind that Claudia persisted because I persisted, and wherever she is, I hope she’s still herself and nothing else.

I’ll still go out of my way to make people feel welcome and happy, but not if they’re gunning for my happiness. I’m still nice, but only to people who deserve my niceness. And I’m still considerate of other people’s feelings, so long as they’re considerate of mine. It took a long time to find that balance, but I like where I finally landed on the tightrope. I like the people that those rules have brought into my life.

It’s also easy for me to think of those other twelve-year-old girls, now women, and forgive them. We were children wrestling with becoming adults in an imperfect world, being raised by imperfect parents, going out into a world that would pay us less, respect us less, while still letting us know that we were too much of something else. We were staging a dress rehearsal for the way society would eventually pit us against one another, and I like to think that we emerged as something better. A ragtag sort of club, if you will, ready to leave the fictional Stoneybrook and take on the world.

Title Far From The Tree

Author Robin Benway

Pages 256 Pages

Intended Target Audience Young Adult

Genre & Keywords Contemporary, Realistic Fiction

To Be Published October 3rd, 2017 by HarperTeen

Find It On Goodreads ● Amazon.com ● Chapters ● The Book Depository

Robin Benway’s beautiful interweaving story of three very different teenagers connected by blood explores the meaning of family in all its forms — how to find it, how to keep it, and how to love it.

Being the middle child has its ups and downs.

But for Grace, an only child who was adopted at birth, discovering that she is a middle child is a different ride altogether. After putting her own baby up for adoption, she goes looking for her biological family, including—

Maya, her loudmouthed younger bio sister, who has a lot to say about their newfound family ties. Having grown up the snarky brunette in a house full of chipper redheads, she’s quick to search for traces of herself among these not-quite-strangers. And when her adopted family’s long-buried problems begin to explode to the surface, Maya can’t help but wonder where exactly it is that she belongs.

And Joaquin, their stoic older bio brother, who has no interest in bonding over their shared biological mother. After seventeen years in the foster care system, he’s learned that there are no heroes, and secrets and fears are best kept close to the vest, where they can’t hurt anyone but him.

4 Responses

Thank god for the girls of the Babysitters Club! They were my everything then, and they still inspire me now.

I loved this. What a wonderful way to start this fab annual series.

It was emotional, impacting, empowering, and really made you think. There were super adorable happy times, and also emotionally-draining sad times. This story had it all. It brought out every emotion in me. I honestly didn’t want it to end.

Lisa @ NatureImmerse recently posted…INFOGRAPHIC – Fun Camping Activities

Oh man, all of this. I wasn’t teased for being overweight but I was bullied for being friends with a girl no one liked for some reason and the BSC books were my escape. Claudia was my favourite too! Bless her quirky, artistic soul.

(I also had a soft spot for Mary-Anne because we were both timid but she eventually grew into a more confident person and my transformation didn’t come until much later.)

I’m so glad to know I wasn’t alone in Stoneybrook. Technically, I knew but I didn’t /know/. Does that make sense? Either way, thank you for writing this.